Aunty Elsie, whose old-style hats and coats meant that she could only ever be Manty Elfie, to me and Bobo, was often an outing in its own right. But I recall it now as the stopping off point on the way to the shore; last but two in the row of houses, one of which seemed never to be occupied, before the Shore Road proper started. It was called something different up to the end of Manty’s row, but we knew it as the Shore Road from the end of Dolly’s street, from the station really. Sometimes we cut straight across the green to go in the back way; other times we had to go to the front door.

We thought of these as Dolly’s foibles. She had all sorts of different protocols for front doors and backdoors. She had two milkmen who were never allowed to meet, even though they came on the same day to collect their money. Most merchants came to the back door, but Butcher New, who was actually a milkman came to the front. Gunther and Bunty, on the other side of the ginnel rendered their front door hors de service by means of an indoor plant holder. Manty Elfie had once done something similar with hers but later relented and thereby introduced an unfathomable etiquette to comings and goings at her house, which were implicitly understood, not to say instituted, by Dolly. I fancied sometimes it was no more than her indulgence of my fear of the troupe of women that we sometimes encountered on the back way into Manty’s. I mistrusted them in their long cloth coats, with their long hair tied back, and their gaggle of children, and their hats. They came from a different time when everyone was old fashioned no matter how old they were.

If you went to Manty’s on the way to the shore it meant there was a reason to leave. You could tell by the way she talked to Uncle Basky, on the rare times he was there, that it was not appropriate to bring anything back from the shore to her house, so we but rarely stopped on the way home. By then we were always eager to get in to see who was closest in our competition to guess the time, and in the summer, how many wickets were down in the Test Match. But I could never estimate the time as grown-ups did.

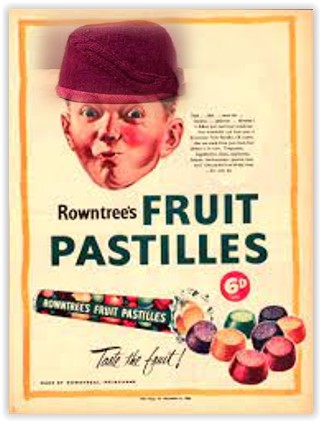

Even if you went to Manty’s on your own you were subject to that same endless nothingness, while you just smiled at each other. She came from a different time when everyone was old fashioned no matter how old they were – perhaps that’s why she never took off her hat. Sometimes she went to the cupboard to get you a square of Bournville, which was good because you didn’t have to think about not speaking for a while, but bad, because when she came back, you’d have to eat it. When I was there with Bobo, we used to hum Rowntree’s Fruit Pastilles! depending on what hat she had on, to make the other one laugh.

I’m only halfway there, but that’s enough for now. I’m tired. I’ll tell you the rest tomorrow.