LEGAL NOTICE

I’ve always believed that the definition of a good childhood, and so the ultimate production of an accomplished, balanced, and happy adult, with the capacity for empathy and joy, who is possessed of self-esteem, moral clarity, and sufficient courage to see all that through, is evidenced, not to say created by their family’s attitude to long car journeys.

There are many of us who hail from families who would approach any long journey with the collective notion that what is about to happen to them is a terrible ordeal to be endured, unfairly imposed upon them, while countless others have been spared it. Yeah, sure, but that’s symptom, not cause. The real damage is done in those confined spaces, where everyone is each other’s prisoner for the duration of the tribulation, and is an environment where some of them do their best work.

The driver who brings his (yes, his) unresolved anger and frustration with him to the driver’s seat, and conducts the journey in a mostly irritated silence which feels to his audience of passengers like an unexplained error they have made, leaving them unable to determine whether their aberration occurred during the journey, or prior to it. The man who is in control of the radio, and whose audible tuts and weary sighs to punctuate the interruptions to the good bits of whatever he’s listening to, removes himself from the social life of the vehicle. He sees the drive as another chore that has fallen to him to perform in his obligation to serve his family, who are blithely unmindful of the sacrifices to his leisure time he makes on their behalf.

Games and songs, to him, a source of second-hand embarrassment, and an unspoken disquiet that they reveal your eldest son to be gay, and lead to a doubling-down of hatred towards your co-parent, whose indulgence and mollycoddling of his otherwise well-bred offspring, has turned them all into soppy, useless, underachievers, who resemble everyone else he hates.

Then there is the passenger who brings her (yes her) abject fear and dislike of travelling to the journey, and conducts it in a resentful silence, intolerant of any intrusion of noise to make worse the torment she is already suffering.

And there is them (yes they), who contrive to make the journey fun, and bring the sort of activities to it that they think they’ve observed in the insouciantly content; and then there are other families, wrong labelled normal, because normal implies a majority, when there are in fact exceedingly few of them, who enjoy their journey in happy anticipation of what’s to come, and have a few time-served staples that serve to increase the happy mood along the way.

Friend John and I were not blessed with families, but we became each other’s, and over our time and long journeys together, we’d developed a reliable set of go-to’s with which we whittled down the empty hours to places unknown. Looking back from this point in history, we should have got married, and adopted a couple of war orphans. It seems ridiculous now, I guess we let the fact that we weren’t gay steer us away from a same sex marriage.

We had just passed the turn off for Otley when we called time on imperfective/perfective verbs of similar spelling, and our conversation moved on to logistics, particularly the plan to refuel. We’d discovered by then that we were driving a hybrid car, rather than just electric, but Friend’s preference was to charge rather than fill up, so that we might save a little to of our cash. He had acquired a float of five-hundred quid from Collings before the journey began —it explained why he’d worn, and was still wearing Colling’s jacket and cap —he’d first put them on for the ATM transaction, in case of cameras.

And that was what concerned us about a recharging transaction. For one, neither of us knew how it was done; for two, we were convinced that the charging itself must leave its own digital audit trail; and for three, it was hard to imagine that such new constructions would come without CCTV. Nevertheless, we persisted in our search, determined to check one out at least, before making our final decision. We took a slip road from the A1 and went in search of one in the depths of the countryside. Friend decided that if we passed a likely place, we’d drive beyond it, then come back, a little while later, to make it look like we were heading south. We’d take precautions, I’d be dropped off, and Collings would be left trapped in his space, so that Friend could conduct any transaction plausibly passing himself off as Collings, travelling alone. A reasonable idea, but one which, if the transaction did leave a digital record of our car’s position, would still give us away. At worst we’d be done for; at best it gave us a few day’s advantage over anyone looking for us.

“What was that?” asked John. The lights had started flashing on the car’s dashboard. He meant the old shack with a light on, that we’d just driven past, not the car that had then started to go through the machine version of a panic. He pulled in to an unlit layby and stopped.

We were deep in the countryside without a street or house light to be seen. In the silence, Collings stirred. We exchanged a glance. I shook my head at John to say, ‘Don’t listen to him.’ You forget about the traits of people like him when you cease to spend time in their company. He was of a type with Scrubber’s Haircut, who Friend had also made disappear a little while ago. It’s a feature of arch fantasists and bullshitters that’s often overlooked —their love of delivering bad news, and pending disaster. It’s where they live on the spectrum of life —positing themselves as the conduit through which the news of change comes first. Gatekeepers even, to the coming disaster that will be ruinous for all of us.

“I’m going back to check it out,” said John. He reached into the back seat to grab the petrol can. “Look after him, ‘til I’m back,” he said, as he got out of the car.

Collings adjusted himself, and made what once would have been called a gurning noise. Friend gave him a very sweary, very scary command to behave himself until he returned, but he continued to make the noise, as if he was trying to communicate something. In the end we discerned a sound which we thought resembled, “Aspirin.”

“Yeah, maybe, if you’re a good boy,” said Friend. He closed the door, pulled down the peak on his cap, stood up the collar, and set off into the blackness. But Collings kept up his low murmuring groan, even after he’d gone. Eventually, to shut him up, I got out of the car and went to the back seat to see if he needed making comfortable. I got him to sit up a little, whilst keeping him in the well, then gesturing towards the glove compartment, he lisped “Aspirin,” again, through his injured mouth.

There were two paracetamols left in a packet. I put them into his mouth, one at a time, gave him a sip of water with each, then left him. I was curious to know what Friend had done to him, and how. I’d seen him in action before, of course, but there was something unusually compliant about him that itched my curiosity. I mean, he didn’t know yet that we were just going to let him out in some miles from anywhere location, to make his own way back. We hadn’t discussed much about the details in his hearing on the way up. So, I guess he just assumed the worst. And I didn’t want to give anything away by asking too many questions. But he looked damaged and sore.

When I was sure he’d swallowed them, I let him slump back into a lying position, and left him to sleep. Outside, I zipped up my coat, tucked my trousers into my socks, and quietly got back into the passenger seat, hoping for half an hour’s desperately needed sleep before John returned.

It seemed like a moment later, when I blinked awake. John hadn’t returned, but something had knocked the car, a nocturnal animal perhaps. Cheated of sleep, I reset myself for another. I pulled up my hood, and as I did, I noticed Collings looking at me in the mirror. I suppose you’d call it grinning. Well, that serpent’s smirk he has, his broken mouth widening it to its best effect somehow. He had a re-booted look about him.

“So, you’ve come to this have you?” He lisped still, from his injuries, but he was more coherent now.

“What?”

“You —a bum. Who’d have thought it? Apart from anyone who really knows you.”

Steady on Steerforth, that’s a bit rich. I mean, I can say it, he can’t. You’ve got to be in the club to come out with stuff like that. And he was not one of my patrons —there’s lots of us, don’t forget, not just me. He didn’t know yet that we were just taking him away to leave disorientated miles from home. I think he believed that a worse fate was attending him.

A bum? I happened to be chasing down the return of my £200k in the firm for which he now clerked. What is more, I came within a few days of being his MP. A bum? What? Compared to him?

“Yeah, go on,” I said, apart from anyone who really knows you? What does that mean? I know you, for example, and you’re a prick with a chip on his shoulder. Do you mean that sort of bum? Someone who’s principal satisfaction in life has been derived by undermining the chances of others? You’re a fucking skunk, and now, in the moment of receiving your justice it is too late to start telling us that we have failed in life. Shut up, and suck it up.”

He said nothing. Why would he? He’s a fuckwit with an ego, who’s never read a book. He’s probably never even watched a challenging documentary. I got out the car, and looked about. It was cold. A pitch-black sky. A faded moon in a faraway corner given far too much to do. Otherwise, the distant glow of blurred and dusty stars. No other light. I set off in the direction Friend had gone, then turned back after fifty yards. Not a sign of him —he’d probably just appear from behind a hedge, unseen from the road.

Phone contact was out of the question, but I stayed outside. No appetite to engage with the nobody inside. Hoping he’d either fallen asleep, or was alert enough to make a bid for freedom which would justify me kicking him under the chin as hard as I could.

Ten minutes later, cold, bored, distracted by thoughts that had kicked into their sundowner cycle, I got back in.

He was waiting for me. Sitting up. Alert.

“Still can’t hack criticism, can you?”

Listen to him. “Shut.. The… fuck… up. No one’s interested.”

“…goes with the territory.”

Friend had that knack of handing out short, sharp physical ripostes to prevent his quarry from getting too uppity. I just didn’t have that in my repertoire. My choices were to have them feel judged by silence and indifference, or to vanquish them with a pithy one liner. Invariably, I chose the wrong one.

“If you’re trying to justify everything you’ve done – it’s too late. You’ve got an audience of one, me, the target of your wrath, and I’m not listening. I know you don’t like me – boohoo, but don’t forget, I’ll always have two things over you…”

“Oh yeah, what are they?”

“I’m not a snake.”

“And?…”

“Or, …a cunt.”

“Still the smartest kid in the playground though, aren’t you?”

It was too cold to get out, there was no sign of John, all I wanted to do was to get five minutes uninterrupted sleep before he returned. And this slimeball suddenly wanted to have an argument with me. He’d never been upfront with me in his entire life. His whole moral construct had him live a life behind other people’s backs. “I don’t care. I am beyond ignorant conversations like this. I left them behind a long time ago.”

“Always smarter than everyone else around you, weren’t you? But you’re the only one of us who’s left nothing behind.”

He’s like getting something stuck on your shoe. Previously, he’d been someone with self-knowledge of ignorance, kept his counsel, did his dirty work behind the scenes. But now, out of nowhere, it was as if he had something prepared. Like a festering bubble of hate, he’d kept inside and honed into the judgment he needed to get out. It was as if, to him, I’d lived a life in blissful ignorance of the arsehole he knew me to be, and he was determined to have me know it, finally. As if he spoke for a whole community. I guess he thought he might be facing his final moments and needed to get it out.

“… well does your CV match your great intelligence now?” he said.

To tell you the truth, that was quite an astute observation. Unless, of course, I’d been the subject of his life’s project, and there’d be apps, programmes, scrapbooks, and a Situation Room, devoted to the study of me, back wherever he lived.

“Your great superpower. You came top in a few tests, sometimes without even revising —ooh weren’t you smart? All achieved between the ages of 9 and 12, and from that, you decided that you were the cleverest one amongst us. Forever.”

What was he on about? He could have gone to university if he’d wanted, but either he wouldn’t or couldn’t. It wasn’t the guaranteed domain for me and my type —we just preferred and chose that life, and the future that went with it. If I went, son of small-minded twat; he, only offspring of ambitious dickheads could have done the same.

“Yeah, that’s right. Have a look at the competition. It wasn’t difficult.”

He sort of smiled, nodding, as if we were sparring like good old foes going at it in the debating society. “You spent the other 90% of your life avoiding failure like it was radioactive. Things you didn’t know —they were for stupid people. Questions you couldn’t show off about —you avoided like the plague, in case they exposed you to be just like everyone else. You weren’t the smartest, and you couldn’t handle it, when you found out. And meanwhile, the rest of us, because we’d learned to confront what we didn’t know, and we’d taught ourselves how to learn it, and improve, well we caught you up, and passed you by. Meanwhile you were still sat on the sides, watching, in denial, dismissive about anyone who proved a threat to you – cos they weren’t smart like you. Still counting up your 10 out of 10s from back when you were 10 years old.

Hold on a minute. I grew up knowing that I was smarter than pricks like him based on empirical evidence, not an assumption of entitlement. He knew fuck all, and I knew how to deploy LOGIC. I’d been taught. There was a graph for it.

“They don’t count now, your ten out of tens! They never counted.” He did his best to shout.

The pithy putdowns deserted me for a moment, and the ensuing silence didn’t feel quite as condemnatory as I’d have it.

“It didn’t do us any damage to say, I don’t know the answer. But it was fundamental to the version of you that you’d constructed for yourself. Have you ever gained the courage to say, ‘I don’t know’? Well, have you?”

“I don’t know.” He didn’t laugh. Mainly because he didn’t understand that it was a joke.

Friend returned into the silence. “He even had a mini-store,” he said. “What’s the matter with him, stirred, has he? Here you are, give him his paracetamols.”

I told him that I’d given him two, an hour ago, and that you’re supposed to wait for four hours between doses. John was rifling through one of his carrier bags, shrugged, and said, “If he dies, he dies.”

That’s what I meant! That was the sort of terrifying indifference that I just couldn’t grasp.

He’d found the map book he was looking for, and began studying, entirely unsympathetic to our hostage. He looked up, and said, “What’s the matter with you? He’s behaved, hasn’t it?”

“To be honest, we found some common ground for once.” I could sense Bon-Bon grinning in the mirror.

“It’s a bit late to start being decent,” said John, and went back to his maps.

Now, that really is what I mean. Beautiful. I sensed the grinning stop.

I didn’t speak. I was processing still. And now, with John back, and Collings sacred to speak, I had my longed-for moment alone. It wasn’t the way that Collings said it, but what he’d said. He outed me as an also-ran in life, deluded by a brief moment in the spotlight as an infant. I’d adopted that first moment of reason as my personality, and lived the rest of my life as if I had a destiny to fulfil. A nobody without a purpose. With nothing to lose.

This was the epiphany I alluded to. Then and there I realised. The life I supposed myself to be leading was over. The moment when I left that lowly underachieving, entitled, deluded idiot behind. The moment I began to embrace the real me.

No one transforms like that, in an instant, I know. Damascene revelations I’ll grant you; Damascene conversions —do me a favour You’ve still got all your old habits and instincts floating round in your viscera. But looking back from where I’m writing this, that was the moment it began. It was from where I took the first steps on the road to becoming a person motivated only by self-interest. Perceived self interest in the very moment in which they lived. No thought to the future, no thought to nuance, compromise, detail; no thought to achieving success by reasoning and proof and merit. It started there, with the revelation Collings gave me.

How did it manifest in that moment? I don’t know. Only that I tried to dissuade myself from the tiniest trace of guilt about what we were about to do. As soon as the thought came to mind, I dismissed it, and made myself think instead about how he’d set me up to destroy my reputation that night.

Of our plan to deposit him on some faraway hill, and leaving him to contemplate his fate and situation, two things, I suppose: that we were about to gain leverage over Eggo in the pursuit of our money; and that I’d soon deliver some tangible revenge to someone who’d knowingly set out to reduce my life chances, in a way he’d comprehend. And better still, have the time to think about it.

Was that proportionate?

I don’t know whether you could say that, exactly, but I no longer cared. And in what was left of this trip, the new me, who had been made aware, as never before, that he had nothing to lose, had plenty of time to weigh up the rights and wrongs of what we were about to do.

Next: Richard Hannay and his quarry, cross into Scotland. Stay tuned.

Yes, I don’t think people here in the US understand TCP. I’ve asked my British friends – it’s like an antiseptic liquid that’s rubbed on cuts and grazes, and is also gargled!!! It’s most like Betadine I suppose. I think it’s a bit dated there now too, from what they say. And that thing about it’s strange aroma – I now know why some people say of some well regarded single malts, that they taste of TCP !!! Thank you for that.

LikeLike

🤣

LikeLike

Me, I like Petisse Sieg Heil. There was always something I thought when I saw his raw oily skin – and that’s it. He’s like someone who smells of TCP (do only British people of a certain name know what that is?).

LikeLike

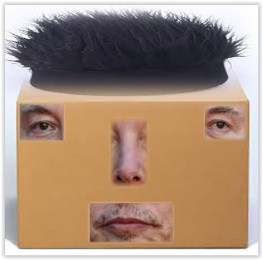

K-hole Bokx!! 😆 100%. And the face! Just like his cyber truck. But my favourite bit – the way his eyes are in each corner. The way a child would draw it. The way he designed his cyber truck actually.

LikeLike